After being an educator in Alabama for more than 30 years, mostly working with students of color from low-income families, I decided I wanted to share what I’ve learned over all those years with school leaders who work in similar settings. By this time next year, I should have finished my research for a doctorate in education on a subject I know well: the lived experiences of minority principals leading school transformation at high-poverty, low-performing secondary schools.

I’m pulling together my research and interviews with other school leaders and all that I’ve learned from my own career, which includes many years as a special education teacher as well as an assistant principal at every level and now the principal of Chickasaw Middle/High School. My school enrolls about 600 students in grades 6–12. We’re a Title I school with a lot of challenges, but we’re there to meet students’ needs. My number one goal is to give our students—whatever pathway they decide to pursue after they graduate—opportunities to be successful.

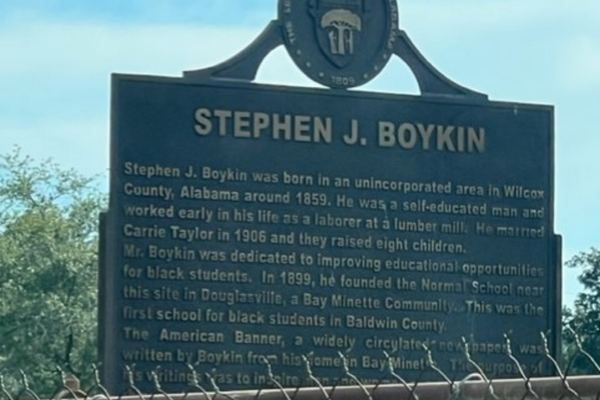

I’m part of a long line of educators in my family. My great grandfather, Stephen J. Boykins, started the first school for black children in Bay Minette, AL, back in the late 1890s. It was called the Booker Industrial School, and he started it to help better the lives of young Black youth at the time. He also published a newspaper, The American Banner, from 1899 to 1902.

In 1899, he wrote a letter to the editor of The Baldwin Times soliciting funds to help open the school. “We believe that industrial education is the best kind of education for the colored youths. It teaches the student the love and respect for labor,” he wrote. “We, the colored people of Bay Minette, are struggling hard to raise funds with which to erect an industrial school building,” he said, noting that they needed an additional $300 to fund the project.

I don’t know a lot about how successful the school was or how long it stayed open, and that’s something I want to research so I have more background for my dissertation. About four years ago, as part of the Alabama 200 Bicentennial Celebration, Baldwin County put up a historical marker at the Douglasville High School Heritage Museum in Bay Minette. One side of the marker outlines my great grandfather’s accomplishments in education, and the other side features the story of The American Banner.

Since then, other members of my family also became educators, including great uncles, aunts, and uncles. That family history is one of the reasons why I chose my doctoral research topic. I’m following in their footsteps in many ways. And now I want to see if others like me share the same day-to-day challenges, including recruiting and retaining staff, closing academic gaps, engaging parents, advocating for more local funding, and strengthening and diversifying the educator pipeline. My ultimate goal for this research is to share my results with current and future school leaders to empower and encourage them by teaching them about the experiences of those who blazed the trail and found some success.

In my own work, I’ve always focused first on relationships. Nobody wants to know what you know until they know you care. So, I want my teachers to show they genuinely care for their students and their futures. Until students feel safe and protected and valued, and they have a sense of self-worth, we’ll never get them to bloom and think creatively and reach their capabilities.

I’m excited about the next phase of my career. Once I earn my doctorate, my goal is to teach educational leadership classes at a local college, like the University of South Alabama. I want to help future administrators of color stay in the profession and keep believing they can make a difference.