Equity Through Grading

With generally high math and reading scores, it can be difficult for school leaders to convince teachers there is room for improvement. But at Ashland Middle School (AMS) in Ashland, OR, we have done just that.

About one-third of the 500 students enrolled in the school receive free or reduced-price lunch, and the student racial demographics are as follows: 71% identify as white, 15% Hispanic/Latino, and 13% multiracial. Achievement data for our English learners, students in special education, and other student populations helped us understand that our traditional system of classroom assessment and feedback was not meeting all our students’ needs.

I (Steve) had worked as an administrator at AMS for seven years, where I had built a strong foundation of trust with the staff and community when Katherine joined as a video production teacher and assumed a leadership role as a Teacher on Special Assignment (TOSA) the year our initiative began. Two years later, we began what would turn out to be a remarkable seven-year run as a stable administrative team when Katherine became the associate principal. This continuity and consistency enabled us to lead a sustained effort to clarify learning expectations, create a feedback loop for students to understand what they needed to learn, and level the playing field so that all students could be successful. We ultimately moved the school from a letter grade system focused on points and percentages to a standards-based proficiency system focused on skills and knowledge.

Why the Shift?

Too often, students want to do well, but they don’t have a clear understanding of what they need to do to be successful. Given differences in learning abilities, background knowledge, and cultural experiences, we recognized that different students access instruction in the classroom to different degrees. For a variety of reasons, many students can easily feel lost. Sometimes they are simply trying to guess what the teacher is expecting.

Using an equity lens, our goal was to maximize learning opportunities for all students. One of the guiding principles of this work was a focus on equal access so that all students could understand the goals of learning. We wanted teachers to pull back the curtain, make the learning clear, calibrate it with their students, and increase accessibility—no matter where the student was starting from.

We remember a powerful moment working with teachers to write rubrics, asking them to clarify exactly what it was they were looking for when evaluating student work, and inviting them to list these qualities in the description on the rubric. One teacher resisted, saying, “But it feels like we’re giving away the answers!” To which we responded, “But isn’t that what teaching is? Isn’t our role as teachers to make it clear to students what they need to do as their next step in the learning process? Why wouldn’t we clearly define what our learning expectations are?”

We believe that if students know what is expected, they are more likely and able to reach those expectations. Too often, students will give up or lose hope simply because they start to feel like they don’t understand what it is the teacher is asking of them.

A “Rubric for Rubrics”

To support this initiative, we leaned on the work of Rick Stiggins (The Perfect Assessment System), Thomas Guskey (“Five Obstacles to Grading Reform”), Joe Feldman (Grading for Equity), Rick Wormeli (“It’s Time to Stop Averaging Grades”), Cathy Vatterott (Rethinking Grading), Laura McKenna (“Will Letter Grades Survive?”), John Hattie (Visible Learning), and Dylan Wiliam (“Keeping Learning on Track”).

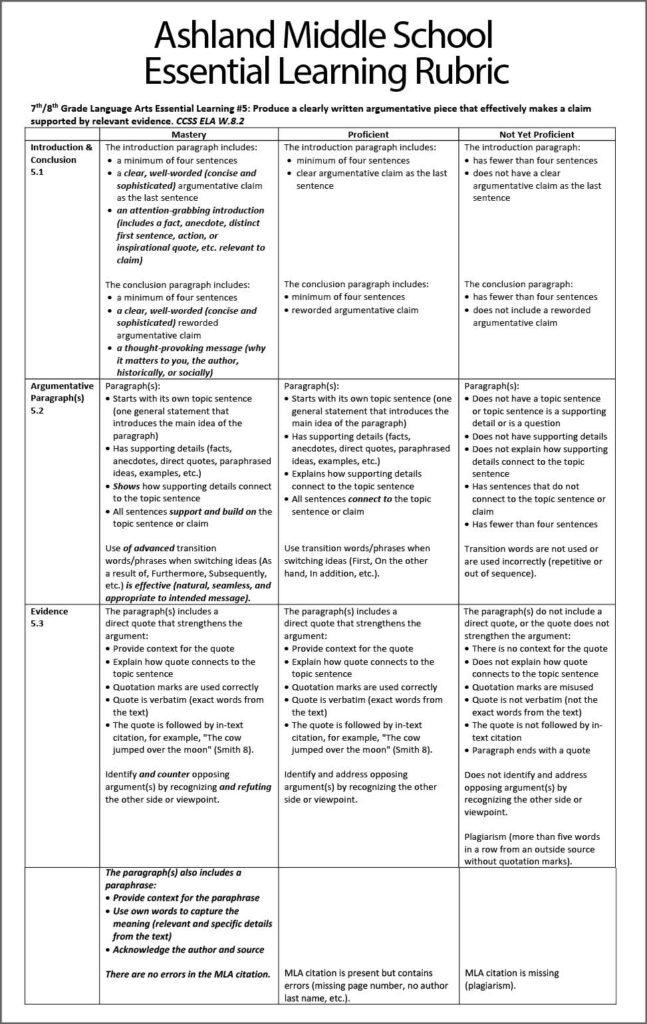

We also developed a “Rubric for Rubrics” which provided teachers with criteria to support them when drafting new rubrics. Many teachers wanted to rely on percentages in their rubrics, but the “Rubric for Rubrics” clarified that, “Percentages are not used to distinguish between proficiency levels.” We also put together a “Rubrics Dos and Don’ts” that outlined examples of rubric language that can impact the objectivity and strength of a rubric.

The guide we created for standards-based proficiency grading and reporting helped to bring new staff up to speed. Many teachers are introduced to some form of standards-based proficiency grading at some point; however, many of the principles that we prioritized at AMS were different. For example, according to the guide, our model is “about clear Essential Learnings and discrete, well-articulated skills and knowledge in student-friendly language at multiple levels of proficiency. It isn’t about providing students with an unlimited number of retakes for each assessment any time a student walks in and wants to take one.”

We found that, given their past experiences, some teachers were skeptical or felt the approach was unrealistic. So, redefining the focus was helpful. Having access to the right tools to track and manage proficiency scores through SmartEd Systems (smartedsystems.org) enabled us to communicate student learning easily to students and parents. As we led more PLC days supporting teachers to develop their essential learning rubrics, we also compiled a facilitators’ checklist outlining steps for building clear and explicit rubrics.

Impacts on Student Learning and Teaching Practices

This system has changed the learning language at AMS. Students now receive one of three proficiency scores: either Mastery, Proficient, or Not Yet Proficient for individual standards-based supportive learnings—those discrete skills that make up a content area standard. Students who demonstrate grade-level work receive Proficient scores, while students who demonstrate additional higher-level skills receive Mastery scores. Where students used to ask their teacher, “How can I raise my grade to an ‘A’?” they now ask, “Can I rewrite the introduction to my argumentative essay?” Students who previously did not see themselves as “A” students now know they can become proficient in any content area. The implementation of standards-based proficiency grading at our school has created a learning environment where students know what teachers expect from them, they understand how they did on their work, and they know what to do to improve.

Student surveys show they value this new approach: 93% say that “Rubrics help me understand what the teachers want me to do on an assignment;” 91% say, “I understand why I got the score I did on an assignment;” and 85% say, “I know what to do if I am not yet proficient on an assignment or test.” The work with PLCs to create transparent and explicit rubrics has shifted the teaching and learning paradigm from “I know it when I see it” to “students know it when they do it.” Since this work first began, student performance on standardized tests outpaced the state average in the five years preceding the pandemic.

With the focus on priority standards and essential learning rubrics in place schoolwide throughout the pandemic, Ashland Middle School showed a significantly lower decrease in standardized assessments in both English language arts and math compared to the state. While the state average dropped by 10% in English language arts and 11% in math between 2019 and 2022, AMS students’ scores decreased by only 1% in English language arts and 9% in math over the same time period.

Lessons Learned

As with any new effort, it’s critical to communicate regularly and often with teachers, students, and families. To that end, we ensured that we shared information regularly about the initiative in our newsletters and end-of-the-trimester mailings. We gave teachers talking points to use at our student-led conferences and surveyed parents and students throughout the process. We also ensured our online resources were up to date and included information, research, examples, reports, and a full bank of our essential learning rubrics so parents could understand this was a widespread initiative to which we were committed.

Anticipating what parts of the change would be met with resistance, such as the transition from letter grades to proficiency scores, was crucial. We took our time easing the community through this change and ultimately empowered teachers to lead it by allowing them to pilot new grading practices early on when they felt inspired to do so. We also prioritized meeting individually with parents who voiced concerns. Through these meetings, we not only helped parents better understand the benefits of this system and clear up any misunderstandings, but we also gathered valuable feedback that influenced improvements.

For instance, a conversation with one parent helped us develop a system to bring back Honor Roll status, even though students no longer had a GPA. Another conversation with a parent led us to add a badge to the online student learning report system, helping students and parents quickly understand what percentage of assignments were being turned in on time or late. Being responsive to parents and their feedback contributed to the success of the initiative.

Supporting teachers with the rubric work took time. Asking educators to change their practice often creates discomfort, so ensuring teachers understood that the focus on this work didn’t mean that what they were doing previously was wrong was important.

Through this process, some staff realized that what they wanted students to learn wasn’t necessarily aligning with what they were teaching. As one of our strongest English language arts teachers memorably said, “Now that I’m so clear on what I want my students to do, I need to go back and look at my instruction to make sure I’m teaching it!”

Katherine Holden is the principal of Talent Middle School in Talent, OR, and the 2022 NASSP Assistant Principal of the Year. Previously, she was the associate principal of Ashland Middle School in Ashland, OR. Steve Retzlaff is the principal of Ashland Middle School.

Sidebar