Fit to Lead: March 2024

Staffing your school with world-class educators isn’t just a matter of recruiting and hiring well when you have a vacancy—it’s an ongoing challenge to create the kind of working conditions that professionals need.

Before diving into what actions school leaders can take to attract and retain talented staff, it’s important to acknowledge the structural challenges of recruitment and retention facing the education profession. These include:

- Fewer people entering teacher preparation programs.

- Stagnating salaries that haven’t kept pace with inflation.

- Competition from other industries, which may offer compensation and perks, like remote work, that schools can’t match.

As an individual school leader, you can’t solve these large-scale challenges, but you can take action to attract talent to your school—and keep people on the job long term. The key is to give teachers the working conditions that produce intrinsic motivation.

Understanding Intrinsic Motivation

First, let’s consider the basic psychological forces: What makes people leave their jobs, and what makes them stay?

Self-determination theory, pioneered by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, identifies three basic psychological needs driving intrinsic motivation:

- Autonomy—the ability to make meaningful decisions for oneself, without being micromanaged.

- Competence—a sense of accomplishment and self-efficacy.

- Relatedness—a sense of connectedness to others.

In high-performing schools with low turnover, these factors may be taken for granted—teachers enjoy autonomy, are seen as competent, and form long-term relationships with their colleagues and community.

All too often, though, the needs of teachers in “low-performing” schools are overlooked out of a misguided urgency to improve learning. Policies intended to increase performance unintentionally undermine intrinsic motivation and drive staff turnover—preventing

lasting improvement.

Consider a school with high staff turnover that has been labeled “failing” based on standardized test scores. What might teachers experience on the job? Let’s consider each of the factors identified by self-determination theory.

First, teachers in low-performing schools are often given far less autonomy than their peers in schools with higher test scores. They may be required to follow much more specific curriculum guidelines, turn in lesson plans, post lengthy learning targets, administer frequent assessments, and generally do what they are told rather than what they think is best. While some of these policies may be educationally sound, their combined effect is to squeeze out the autonomy teachers need to do their jobs and feel like professionals.

Second, when doing as they’re told fails to produce the expected test scores, teachers themselves are labeled failures, despite ample evidence that out-of-school factors play a far larger role in student achievement. Fault-finding approaches to teacher observations and evaluations further erode teachers’ sense of competence.

Third, the constant churn of colleagues and the looming threat of termination or school closure damage teachers’ sense of relatedness. Great people want to stay in schools where great people stay, and sadly, the reverse dynamic is true as well—turnover drives further turnover.

How can we disrupt these dynamics, and create the kinds of schools where professionals can thrive long term? Here are four recommendations.

1. Eliminate Micromanagement and Maximize Autonomy.

Teachers may not have the freedom to determine their own standards or curriculum, but they can exercise substantial autonomy over the many day-to-day decisions of teaching.

In our forthcoming book Cultivate & Activate: Building Capacity for Instructional Leadership, high school Principal Keith Fickel and I recommend cultivating teacher leadership by deferring to those most affected by and most responsible for implementing a given decision. This tends to improve both buy-in and decision quality.

For example, science teachers may have a preferred vendor for science materials, which may or may not match the preferences of the district purchasing department. Since materials and equipment have implications for how teachers conduct their classes, it makes sense to respect their preferences and order from vendors who provide what they need.

Similarly, while curriculum-pacing decisions may be coordinated at the district level, including teacher leaders in decision-making for their subject or department will result in better decisions and greater buy-in than if central office staff make such decisions without involving teachers.

Leaders can also increase teacher autonomy by making fewer demands on teachers, such as requirements to turn in lesson plans. Such requirements may be well intentioned but have the effect of making teachers feel micromanaged rather than trusted as professionals.

Behind every instance of micromanaging is a laudable commitment to excellence, and an admirable interest in what teachers are doing. But these aims can be more effectively pursued with a high-attention, low- control approach.

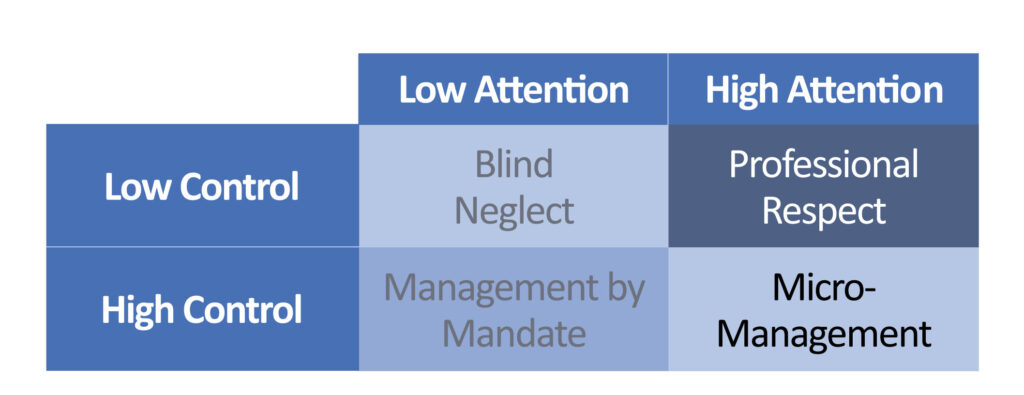

The Micromanagement Matrix below outlines four possibilities for attention and control. With low control and low attention—when leaders don’t know and don’t attempt to influence what teachers are doing—uneven results are the norm, a state of Blind Neglect. To remedy this situation, leaders often increase control without increasing the attention they pay to classroom practice, resulting in Management by Mandate. And if leaders increase both attention and control, they create a situation of Micromanagement.

In these three scenarios, either leaders don’t have the information they need to do their jobs, or teachers don’t have the autonomy they need to exercise professional judgment, or both. The solution is to exert low control, while paying a great deal of attention to teacher practice and teacher voice, a situation the matrix identifies as Professional Respect.

Professional respect gives teachers the autonomy that self-determination theory tells us they need, while giving leaders the information they need. How can leaders hand over the reins, while remaining well-informed about teacher practice? By getting into classrooms without giving negative feedback.

2. Promote Competence With Classroom Walkthroughs.

As I talk with leaders around the country about their approaches to instructional leadership, I frequently encounter tactics and policies that rate, score, and criticize teachers after each brief visit. Self-determination theory tells us that these visits are likely to have a negative effect on teacher motivation, and there is little evidence to indicate that teachers benefit from suggestions for improvement or poor ratings of their practice. Instead, we can defer judgments about teacher practice until the end of the formal evaluation process, and use classroom walkthroughs to pay close attention—showing professional respect—to teacher practice.

In the September 2023 issue of Principal Leadership, I described a high-frequency, low-stakes approach to classroom walkthroughs based on open-ended questions rather than positive and negative feedback. When you visit classrooms, strive to notice what teachers are doing, and when you talk with them, share what you noticed without judgment. Ask open-ended questions, like “Could you tell me more about that?” The more you listen, the more you’ll learn—and the more you’ll show professional respect for teachers and their competence.

3. Promote Relatedness With Leadership Pipelines.

Lastly, you can promote the third factor in self-determination theory—relatedness—by encouraging people to grow as professionals and take on positions of increased responsibility. For example, aides can pursue teacher certification. Teacher leaders can become administrators. APs can become principals. School leaders can take on central office roles.

How can encouraging people to take on more leadership promote relatedness—especially since they may leave? There’s a difference between leaving a school because you’ve grown as a leader and leaving because you can’t grow as a leader without leaving. It’s not just about the people who move on—it’s about why, and the culture you create for everyone who stays.

Organizations that take a fixed view of talent—pigeonholing people in their current roles, without seeing them as capable of developing—will lose people as they grow and seek new challenges. As a result, vacancies must then be filled by outside hires who lack institutional knowledge and long-term relationships.

In contrast, organizations that develop leaders promote relatedness by filling leadership positions with internal staff who already have relationships with stakeholders. Developing and promoting people internally requires intentionality and a long-term commitment to developing people. It’s more work—promoting an internal candidate often creates an additional vacancy to fill—but it’s worth it. Over time, talented educators move up the ranks, preserving relationships and institutional knowledge.

4. Promote Intrinsic Motivation.

There will always be staffing challenges you can’t control, but you can create the conditions that foster intrinsic motivation by:

- Steering clear of micromanagement—paying attention to teachers without taking away the autonomy they need.

- Avoiding negative feedback and excessive ratings of teacher practice, and focusing on understanding teacher practice deeply through open-ended feedback conversations.

- Developing leadership pipelines to create opportunities for people to take on greater responsibility as they grow.

By promoting autonomy, competence, and relatedness, you can create the working conditions the most talented teachers crave and retain them for the long term.

Justin Baeder, PhD, is the director of The Principal Center and the co-author of the forthcoming book Cultivate & Activate: Building Capacity for Instructional Leadership.