Role Call: October 2021

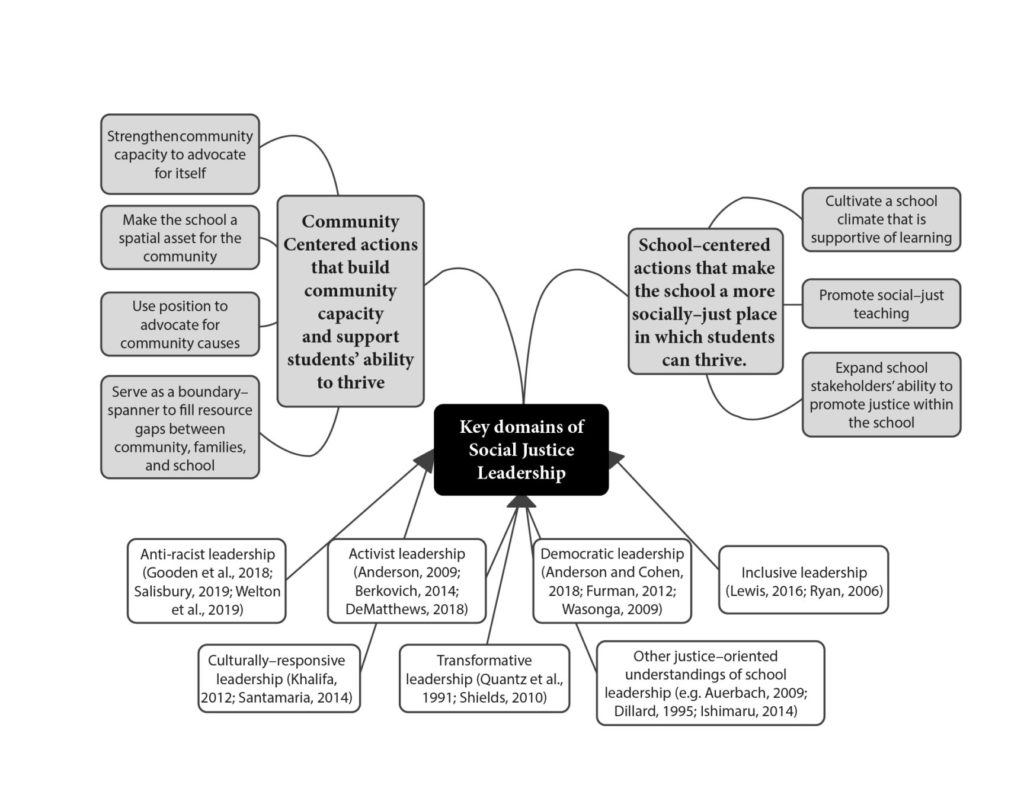

Social justice is a value frequently espoused by our districts, but what does it mean to lead for social justice? Exploring this topic is often more theoretical than practical. To give school leaders a clearer idea of social justice leadership, here are seven key practices, along with real-world examples, drawn from a recent study of seven highly effective school leaders in Chicago. (To protect their privacy, only the leaders’ first names have been used.)

Justice Within the School

School-centered actions are meant to make the school a more socially just place that supports learning, and these actions likely form the bulk of leaders’ work.

Cultivating a School Climate That Supports Learning

Research: To cultivate a school climate supportive of student learning, leaders engage in four main practices. First, they ensure all students feel that their cultures and identities are honored within the school. Second, leaders favor restorative approaches to discipline, which creates a more caring and responsive environment. Third, by eliminating inequitable learning structures, leaders act on the belief that all students can and will learn. Finally, leaders bring community resources into the school to provide students with holistic supports.

Practitioners: Natalie noticed at her previous school—a high school in a low-income area—that there was a large population of pregnant students. She partnered with a community group to establish a health clinic catering to pregnant teens in the school building. She also noticed that many of her students were in legal trouble, so she partnered with a legal aid clinic to provide them in-school support. Natalie said her work “created a space where kids are safe so that then they’re ready to learn.”

Promoting Socially Just Teaching

Research: Social justice leaders promote socially just teaching through two key actions. First, they hire teachers with an eye to their social justice dispositions, subject matter expertise, and diversity. Then, leaders provide them opportunities to develop their critical consciousness and engage in socially just and culturally relevant pedagogy.

Practitioners: Julie leads a school where the majority of students are Hispanic and from low-income families. She said that in hiring teachers, “the most important thing … is teachers’ value set.” She said that while teachers can improve their skills, values are more challenging to change. At another school, Mark engaged teachers in training related to race issues after his school went through a merger that brought in more Black students. In this way, he was directly responding to immediate school needs.

Expanding School Stakeholders’ Ability to Promote Justice

Research: Social justice leaders work with three primary groups of school stakeholders. First, they work democratically with staff on justice initiatives and ensure staff members have a stake in social justice work within the school. Second, leaders partner with families in school decision making and provide them with capacity-building opportunities. Third, leaders cultivate students’ ability to enact their own social justice agendas through curricula and leadership opportunities.

Practitioners: Natalie and Dana encouraged students to engage in action research projects in which they identified problems within the school or community and then conducted long-term projects that sought out solutions. To build family capacity, Betty and Carlos, who both lead primarily Hispanic, low-income schools, held legal clinics to ensure parents understood their rights related to immigration.

Justice Within the Community

Leaders also conduct social justice work in the community because they recognize that the community affects student learning.

Strengthening Community Capacity to Advocate

Research: Leaders have two avenues. First, provide community members with personal development opportunities, such as financial literacy or English language courses, at the school. Second, provide community members a seat at the decision-making table and form community-school committees that center community voices.

Practitioners: When Betty and Carlos hosted legal clinics on immigration rights for families, they opened up these clinics to the community. To support community leadership capacity at his school, Mark trained a group of community members to serve on a school leadership group and gave them a fieldhouse near the playground where they could meet. His goal was to make this group a “community resource” and for members to serve a “positive loitering” function that would make the playground safe for children after school hours.

Making the School a Community Asset

Research: Leaders provide capacity-building opportunities, such as those described above, on school grounds, creating a permeable boundary between the school and community. Leaders also welcome community members to use school grounds and facilities in a way that extends the community’s resources.

Practitioners: Julie has allowed local groups to use the school for “a hundred meetings, probably.” She believes that, as an integral part of the neighborhood, it’s a small contribution. Carlos opened his school to the community in multiple ways, including allowing a local church and local political group to use the auditorium, keeping the playground unlocked, and installing basketball hoops for anyone to use at any time.

Advocating for Community Causes

Research: Within the school, leaders ensure that social justice initiatives begun by teachers or students are aligned to needs and causes within the broader community. Outside the building, leaders leverage their position to actively promote and support community social justice movements by participating in coalitions, testifying for state commissions, and doing similar work.

Practitioners: To align school and community activities, Natalie coordinates school projects to ensure they are “intentional and have a bigger reach schoolwide and do not overlap.” Both Carlos and Dana have advocated with local politicians and builders’ associations to push affordable housing as their neighborhoods are becoming gentrified. Betty has worked “under the radar” to encourage parents to organize and fight for increased safety measures that will benefit the school.

Filling Resource Gaps Across Groups

Research: Because social justice leaders interact with various stakeholders, they can nurture relationships and fill resource gaps across sometimes unconnected groups in a way that allows stakeholders to work together to address needs.

Practitioners: Mark describes himself as a “conduit, like a Grand Central Station,” where he takes information and resources and then connects it to others. Julie’s school sits between two neighborhoods with different demographics; she envisions herself as a voice who could facilitate relationships between both, and now the two work together regularly.

Tips for Success

Are you ready to engage? Below are some tips from the leaders featured above.

Know your school and community. As Mark says, “You have to understand the context of the communities that kids live in before you can serve them.” Carlos advises, “Talk to your teachers and get to know the pulse of the issues in your school. Scout your community and learn about the local politicians, the different businesses, other local principals, and the police beat in your area.” Dana suggests leaders “get involved in the community and figure out who are the informal leaders, who are the players, and how to leverage those relationships to benefit the school.”

Build authentic relationships. Much of this work is built on authentic and reciprocal relationships. Betty recommends leaders “honor relationships and respect them, and don’t just use them for what they can give you.” As Dana says, “People have to know that you genuinely care. … If you don’t have trust with stakeholders and they don’t trust you, good luck.”

Frame and communicate effectively. Sometimes you have to “sell” social justice. Good communication matters, said Natalie: “These resources exist somewhere, and if you tell a good story, people will help.” Julie suggests “finding mutual interests in the success of the school.” Patrick adds that it’s important to “try to figure out your role and what’s going to be most effective,” as sometimes students or parents sell ideas best.

Manage risks. Sometimes social justice leadership can be risky. As Betty says, “There are people who do speak out, and the next thing you know, someone’s on the news and is being walked out.” So, pick your battles. Dana advises being “strategically loud” and “constantly measuring the cost-benefit ratio for yourself, your staff, your students, and your community.” Natalie recommends to “make sure you turn your paperwork in on time and test all your kids. … It just gives you more authority when it is time to ask or push.”

Go Forth for Justice

We cannot achieve justice if we do not seek it. Though your practice may look different from the examples presented here, you can apply this framework in your own school and community. This work can be time-consuming, difficult, and risky, but it is critical for ensuring equity and justice for students and communities.

Meagan Richard is a doctoral candidate in the Educational Policy Studies program at the University of Illinois in Chicago.