Fit to Learn: March 2023

In March 2022, coinciding with Sheryl Sandberg’s announcement she was leaving as Facebook’s COO, The New York Times did a retrospective of the legacy of her book Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. While acknowledging that the book provided inspiration to many, it also highlighted the more problematic part of the book’s message—that, in the end, the only real thing holding women back is themselves. This message, that it is women’s failings rather than systemic discrimination keeping them from accessing and thriving at work, is deeply ingrained in the field of education and helps to explain the continued underrepresentation of women in the education leadership ranks. We need to stop asking women to change themselves and start taking a more critical look at how the profession limits women’s access to, and ability to thrive in, leadership roles.

Women in Education Leadership by the Numbers

In 2018, 76% of teachers were women, and only 57% of elementary school principals and 36% of high school principals were women. Given that high school leadership is often a stepping stone to the superintendent position, it is perhaps not a surprise that women’s representation grows ever more meager as one moves up the ranks; only 27% of superintendents today are women, a percentage that has barely budged in 20 years. This underrepresentation is even starker for women of color. For example, in 2018, only 6% of principals in U.S. public schools were Black women. In 2022, only 10% of superintendents identified as African American, with the number of women within that group being difficult to ascertain from public databases. The bottom line, of course, is that there are too few.

Understanding This Underrepresentation

While the reasons for this underrepresentation are numerous and complex, they are not due to a lack of women’s will, capability, or confidence to engage, but rather systematic failures in infrastructure to support women’s professional lives. This lack of support became undeniable when COVID-19 disproportionately affected women and their work. Given that 20% of teachers—approximately 200,000 women—have children under the age of 5, and many others have school-aged children, we can imagine how poor childcare infrastructure would impact a woman’s decision to move up the education leadership pipeline. As women frequently hold care responsibilities beyond those of raising children, the same constraints are also likely true for female educators with aging parents or other loved ones for whom they are the primary caregivers. Indeed, while more women are working and serving as the family’s breadwinner than in any other time in history, they still hold the bulk of domestic duties—providing them less flex time or, for those considering education leadership, less ability to attend the multitude of after-school and weekend events that school and district leaders are so often called to engage in.

Additionally, though often less discussed, is how gender discrimination and gendered racism (i.e., the compounded racial and gender discrimination women of color experience) is deeply ingrained in how we conceptualize leadership in education. Many of our policies and rhetoric uplift the notion of a heroic leader swooping in and, through force of will, turning a school around. A multitude of cross-disciplinary research points to effective leaders exhibiting care, building trust, and sharing power and decision-making. Putting aside that the hero-leader working in isolation does not display those traits of effective leadership, this vision of leadership also elevates stereotyped male (and white) characteristics of risk-taking, aggression, and decisiveness and deemphasizes those that are stereotyped feminine (e.g., caring, emotionality, connection, etc.).

Therefore, although women leaders are shown to be more likely to possess the effective leadership traits named above, they often find themselves in a double bind: They can embrace the stereotyped male characteristics associated with the more heroic version of leadership and thus violate perceptions of feminine behavior (e.g., she’s mean, aggressive, etc.), or they can engage in more stereotyped female characteristics but fail to match the perception of leadership (e.g., she’s too emotional, she’s weak, etc.). In other words, women are forced to play a rigged game in which the ability to win remains beyond their control.

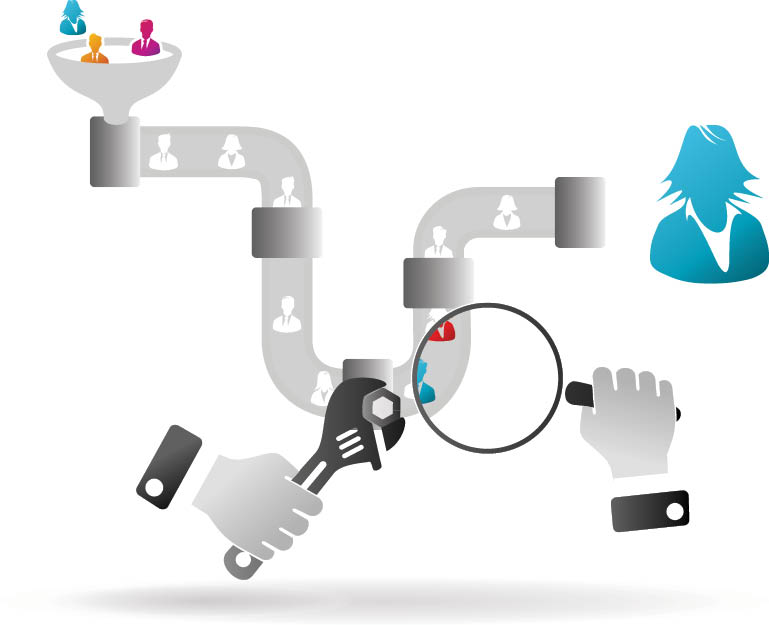

This notion that leadership requires stereotypically masculine characteristics is not only pervasive for the principal position but throughout the education leadership pipeline. First, white male teachers often receive far more mentoring opportunities than their female counterparts or colleagues of color from those in power (also mostly white men). As being “tapped” remains the predominant means of gaining leadership opportunities, it helps to explain why women take far longer to obtain such opportunities. Second, recruitment and hiring materials often include gendered or racialized language and criteria that emphasize “potential” or “fit” over skills and knowledge—a practice that tends to reinforce existing bias and thus limits women’s access to leadership. Finally, when women are hired as leaders, they are often placed in the least resourced and underperforming schools. This phenomenon, called the “Glass Cliff,” is particularly true for women of color who are positioned as fixers or “clean-up women,” often without the necessary support to succeed.

Even when women do beat these incredible odds, they often face tougher performance expectations than their male counterparts or see their achievements discounted. As a result, and lacking alternative means to explain these experiences, capable female leaders often begin to internalize such critiques, questioning themselves and their skills in the process. Others build up various coping mechanisms that allow them to persist but are costly to their psychic and physical energy. We need a better path forward in which women’s capabilities and contributions can be fully actualized, appreciated, and sustained.

Building an Equity-Minded Leadership Pipeline

There are many ways to improve the opportunities and outcomes for women leaders. If you don’t have the authority to lead such efforts yourself, advocate for specific practices in your organization. Here are just a few to get started:

- Preparation: We can and should be doing a better job providing resources to aspiring female leaders about how their identities shape both their approach to leadership and how others will respond to their efforts and strategies to persist and thrive. My colleague, Professor Monica C. Higgins, and I created such a resource, our forthcoming book from Harvard Education Press. It includes opportunities for candid conversations about how gender and racial bias shape women’s experiences and challenges the idea that leadership is identity neutral and that women who do not meet existing standards are the “problem” rather than the system itself.

- Recruitment and Hiring: In addition to personally reviewing recruitment and hiring materials to ensure the absence of gendered or racialized language (or pushing for others to do so), it is important to identify and use specific hiring criteria grounded in research on effective leadership practices. No longer should a general sense of “fit” be used to fill leadership positions. More ways to enhance hiring practices and make them more equitable can be found in Iris Bohnet’s book, What Works: Gender Equality by Design, an important resource for anyone hoping to encourage or advocate for women’s success at work and their ability to thrive in leadership.

- Horizontal Mentoring: Women can gain tremendous resources and support by engaging in affinity groups aimed at informal mentoring and support. These groups can fill in where traditional mentoring may be absent, and they are particularly important for women of color who may be isolated in their community and thus need opportunities to speak with those who have had similar lived experiences and feel safe in doing so.

- Ongoing Bias Training: While the above actions can help move us toward a more equitable pipeline and positive experience for women seeking and working in leadership, discriminatory beliefs run deep and must be regularly and vigorously attended to. Schools and districts need to add training on gender-based discrimination into their larger Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion efforts. Such training might include opportunities to learn about and disrupt gendered and gendered racial microaggressions or to audit current policies to ensure they meet gender-equity criteria. Doing so may go a long way in removing the burden of fighting discrimination from those being targeted and instead push those with power and privilege to lead these efforts.

Conclusion

It’s time for the education system to allow women to stand straight in their leadership capabilities by embracing new and more equitable models of leadership. Only then will we achieve the equitable opportunities and outcomes female leaders, our schools, and school systems so deserve.

Jennie M. Weiner, EdD, is an associate professor of educational leadership in the Neag School of Education at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, CT, and co-author of The Strategy Playbook for Educational Leadership: Principles and Practices, as well as a forthcoming book on women in K–12 education leadership from Harvard Education Press.

References

Bohnet, I. (2016). What Works: Gender Equality by Design. Harvard University Press.

Gardiner, M. E., Enomoto, E., & Grogan, M. (2000). Coloring outside the lines: Mentoring

women into school leadership. SUNY Press.

Ibarra, H., Ely, R., & Kolb, D. (2013). Women rising: The unseen barriers. Harvard Business

Review. 91(9), 60–66.

Weiner, J. M., & Burton, L. J. (2016). The double bind for women: Exploring the gendered

nature of turnaround leadership in a principal preparation program. Harvard Educational Review. 86(3), 339–365.