A Coaching Approach to Leadership

One of the most important tasks leaders engage in is helping teachers reach more of their potential. When a principal helps teachers improve how they teach, for example, that improvement directly translates into better outcomes for students because better teaching leads to better learning.

One of the most important ways to help educators improve is coaching. Leaders who understand and apply a coaching approach to leadership will be more effective because they will be better able to tailor their interactions to meet the unique strengths and needs of teachers and students. In this article, we provide a quick introduction to a coaching approach to leadership by explaining what coaching is, why it is important, and how to do it.

What Is Coaching?

We like to define coaching as a one-to-one, goal-directed, managed conversation designed to unlock potential and build capacity through partnership. This definition calls for some clarification. First, while team coaching certainly exists, this article focuses on one-to-one coaching interactions. Second, coaching is a managed conversation. This means coaches use a conversational framework and specific skills (described below) to help teachers achieve their self-defined goals. Third, coaching is goal-directed. In other work, I (Jim) have described effective goals as PEERS goals, which are:

- Powerful: Goals should have a significant, positive impact on student learning, engagement, or well-being.

- Easy: Although challenging, goals should be as simple to implement as possible.

- Emotionally compelling: Goals need to resonate emotionally with teachers.

- Reachable: Goals should be measurable and achievable through a clear strategy.

- Student focused: Goals should involve measurable changes in student achievement.

Finally, coaching is not about dispensing advice; it’s about fostering growth through partnership. To understand coaching as a partnership, let’s look at three primary types of coaching interactions.

Three Approaches

1. Facilitative Conversations: During facilitative coaching conversations, the coach assumes that teachers have the knowledge they need to address the issue at hand. Coaches see their role as helping teachers translate that knowledge into action. Coaches using this approach set aside their own ideas and opinions to listen and ask questions that empower teachers to set meaningful goals and create useful plans. The facilitative approach builds efficacy and boosts motivation, as teachers work on goals they care about. However, this approach has limitations—teachers may not always have the knowledge they need to address certain challenges. In such cases, a different approach is required.

2. Directive Conversations: In directive conversations, leaders provide teachers with specific actions they need to take. This approach is helpful for conveying clear expectations, addressing unprofessional behavior, or shaping organizational culture. However, the directive approach can sometimes oversimplify the complexities of teaching, overlook teachers’ expertise, and reduce motivation by positioning the teacher in a subordinate role.

3. Dialogical Coaching: In dialogical coaching, the coach shares ideas only when needed and does so in a way that empowers teachers to think independently. This approach combines the benefits of the facilitative approach with the opportunity for teachers to acquire new knowledge if necessary. However, dialogical coaching has its own challenges. Coaches can slip into the directive approach and offer ideas too readily, overshadowing the teacher’s voice and potentially hindering the teacher’s own problem-solving.

Why Coaching Matters

Coaching is an effective process for helping teachers grow and improve. One of the greatest benefits is that it interrupts the constant busyness and urgency that can dominate teachers’ day-to-day work. By stepping outside the immediate demands of their classrooms, teachers are given the opportunity to pause and think deeply about the challenges or opportunities they face.

In addition, coaching provides teachers with support and an alternative perspective. Coaches ask questions and sometimes share ideas so that teachers can have an outside view that helps them reframe situations and discover new possibilities for action.

One of the most valuable aspects of coaching is that it is individualized. Unlike one-size-fits-all approaches to professional development, coaching addresses the unique needs and strengths of each teacher and their students. Furthermore, coaching is agile, providing teachers with the time they need to remember, learn, and adapt strategies in ways that work best for them. Rarely does an off-the-shelf strategy succeed without some modification. Coaching allows teachers to work in partnership with their coaches to make these necessary adaptations, ensuring that the strategies they implement are well-suited to their specific contexts.

Coaching also builds capacity and fosters independence in teachers. A well-executed coaching partnership enables teachers to solve their own problems, which fosters resilience and self-reliance and builds motivation. As teachers grow more independent, they are better equipped to navigate challenges on their own.

Finally, coaching strengthens relationships. Effective coaches are skilled listeners who genuinely appreciate the teachers they work with. Through collaboration and mutual respect, coaching fosters trust and deepens the connections between coaches and teachers.

How to Do It

Coaching conversations are often loosely structured around a coaching framework. This is not an outline to be followed to the letter. Still, when coaches keep a framework in mind for their conversations, they are usually more effective and efficient. Here, we focus on two coaching frameworks: one for facilitative coaching and one for dialogical coaching.

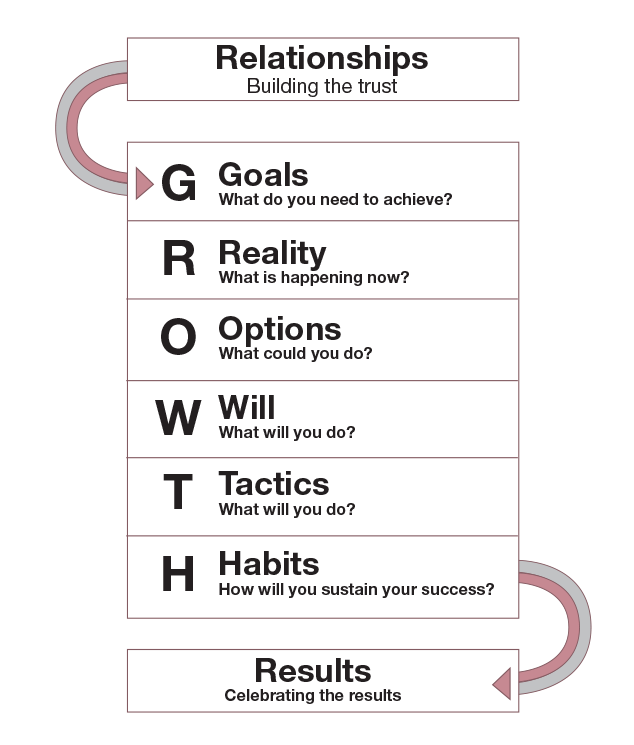

Facilitative Coaching: The GROWTH Model. This framework involves eight steps, which authors John Campbell and Christian van Nieuwerburgh describe as “a form of scaffolding” that supports a teachers’ exploration of meaningful change. A GROWTH coaching conversation is grounded in a trusting relationship between a coach and teacher. Together, they identify a goal the teacher would like to hit and explore options for the teacher to hit the goal. Then, the coach asks questions to help the teacher identify what they will do. Then, the coach prompts the teacher to identify tactics, the action steps they will take to hit the goal, and what habits the teacher might need to adopt or change to succeed. Finally, the coach and teacher discuss how they will celebrate when the goal is met.

Dialogical Coaching: The Impact Cycle. Elsewhere, I (Jim) have written about “The Impact Cycle,” a model for change that my colleagues and I developed over a 10-year period of research and development. The impact cycle involves a deceptively simply conversational framework involving three stages: identify, learn, and improve.

During the identify stage the coach partners with a teacher to identify their current reality (perhaps through video or interviews), a PEERS goal, and a strategy the teacher will implement in an attempt to hit the goal. Then, during the learn stage, the coach ensures that the teacher is ready to implement the strategy by discussing the strategy dialogically (see the image on page 41) and offering a chance for the teacher to see the strategy in action. Following this, during the improve stage, the coach partners with the teacher to explore what modifications must be made until the goal is met.

Coaching Skills

Asking powerful questions is a crucial part of coaching. Great questions are clear, concise, and focus on the teacher rather than the coach’s expertise, empowering teachers to find their own insights. These questions inspire hope, highlight strengths, and encourage a positive view of the future. “Great questions,” as author Julie Starr writes, “avoid making somebody wrong.”

Effective questions are thoughtfully chosen to suit the moment and reflect genuine curiosity rather than scripted manipulation. These questions clarify teachers’ options, help them see actionable next steps, and create clarity that fuels their energy and motivation. By helping others think deeply and see from alternative perspectives, a well-timed question moves the conversation forward, supporting teachers as they plan, learn, and grow.

1. Listening may be the most discussed and least implemented leadership coaching skill. Fortunately, effective listening is a skill, and anyone can get better at it. Listening essentially involves an internal and external component. Internally, effective listeners stay focused on what their conversation partner says by letting go of the need to make assumptions, to make judgments, or to plan their next question while the person is talking. To really listen, coaches need to stop the distracting thoughts in their heads so they can think with their conversation partners.

2. Externally, good listeners look like they’re listening. That means they don’t interrupt or complete people’s sentences. They turn their bodies toward their conversation partners, and they make an appropriate amount of eye contact. They don’t fidget, or check their watches, phones, or computers. They simply listen because they care, and they’re interested.

Take a dialogical approach. When coaches take a dialogical approach, another critical skill comes into play: engaging in dialogical interactions. To do this, coaches must clearly communicate their ideas while also ensuring that the other person feels free to make their own decisions. Ultimately, people only choose to do what resonates with them, and a dialogical interaction invites them to say what they think openly.

Dialogical coaching is a collaborative process that engages both people in the conversation. Coaches don’t support teachers effectively by withholding ideas that could be helpful. However, neither do they serve teachers by dictating what to do without seeking input. A dialogical approach balances telling and asking, creating a space where both perspectives are valued. This balance becomes especially important when teachers are working on setting goals, selecting strategies, or learning new teaching methods.

Final Thoughts

Anyone who leads will find themselves addressing situations where a direct conversation is necessary. However, leaders will also find themselves in situations where a coaching approach is more effective. The best leaders know when to direct and when to coach. When leaders respect and adapt to the uniqueness of each individual teacher, they help them realize more of their potential. And when teachers grow, so do students.

Jim Knight, PhD, is the co-founder and a senior partner at the Instructional Coaching Group and a research associate at the Center for Research on Learning at the University of Kansas. He is the author of several books and articles on instructional coaching and professional learning. John Campbell is founding director of Growth Coaching International, where Christian van Nieuwerburgh is a consulting professor. Learn more at instructionalcoaching.com and growthcoaching.com.au.

References

Campbell, J., & van Nieuwerburgh, C. (2018). An introduction to leadership coaching: Creating conditions for effective learning. Corwin Press.

Knight, J. (2018). The impact cycle: What instructional coaches should do to foster powerful improvements in teaching. Corwin Press.

Starr, J. (2016). The coaching manual: The definitive guide to the process, principles and skills of personal coaching. FT Press.